The thing about visiting Japan is that you can’t afford to sleep in. Cultural sites open

as early as they close and by 5pm, your visits will probably be over already.

Of course, Japanese nights can get pretty hectic if you choose to pull an

all-nighter at a karaoke booth, if you try to visit every convenient store

around in a row or simply if you want to take a night walk surrounded by neon

lights. Yet, temples and shrines will mostly be off-limits by the late

afternoon.

This was a fact we had gotten accustomed to. Still, with only one afternoon in Kyoto, it

seemed a daunting task to visit some of the city’s most famous cultural

landmarks. We had managed to cram in a few in our program but our feet were not

fast enough to take use to the ones that closed at 4pm or the ones that were

too far from the city centre. The golden splendor of the Kinkaku-ji temple was

out of reach and so were the thousands of vermilion gates of the Fushimi Inari

Taisha shrine. At least, that’s what we thought.

I had been to the Fushimi Inari Taisha before and faintly remembered that the shrine was

actually an open-air site without clear boundaries, which could be accessed

freely. It occurred to me that, if such were the case, it might still be opened

at night. A simple Google check confirmed that it was open 24 hours a day,

reviving our hope. From the Kyoto station, a mere 10-minute train ride would

take us to the shrine.

Trains were full of local commuters coming back home from work and we were the only ones to get off at the tiny station of Inari. Night had fallen onto us fast and it was

already pitch-black all around but the illuminated red gate that stood across

the station left little room for confusion. As in my memories, there were no

ticket booths of any kind or any restriction to access the site. One thing had

changed though. There was no crowd.

Located on the aptly named Inari Mountain, the shrine was popular with joggers and hikers

by day, not to mention with massive crowds of tourists and local worshipers.

By night, it attracted the occasional foreign tourists, like us, too happy to

claim the site for themselves. There were also a number of local night birds,

teenagers rushing through the gates towards the top of the mountain and older

couples stopping by every building to pray. In total however, we didn’t meet

more than a dozen people.

Following a great many statues of kitsune, mythical foxes traditionally seen as messengers

and typical of Shintô shrines, we went through the main gate and made it to the

main hall of worship called the haiden. Built in 1499, it was guarded by yet

another kitsune. By night, the red and white colors of its structure shone

even more brightly, illuminated by a series of ornate lanterns. A few stairs

beyond, a smaller shrine marked the entrance to the highlight of the shrine,

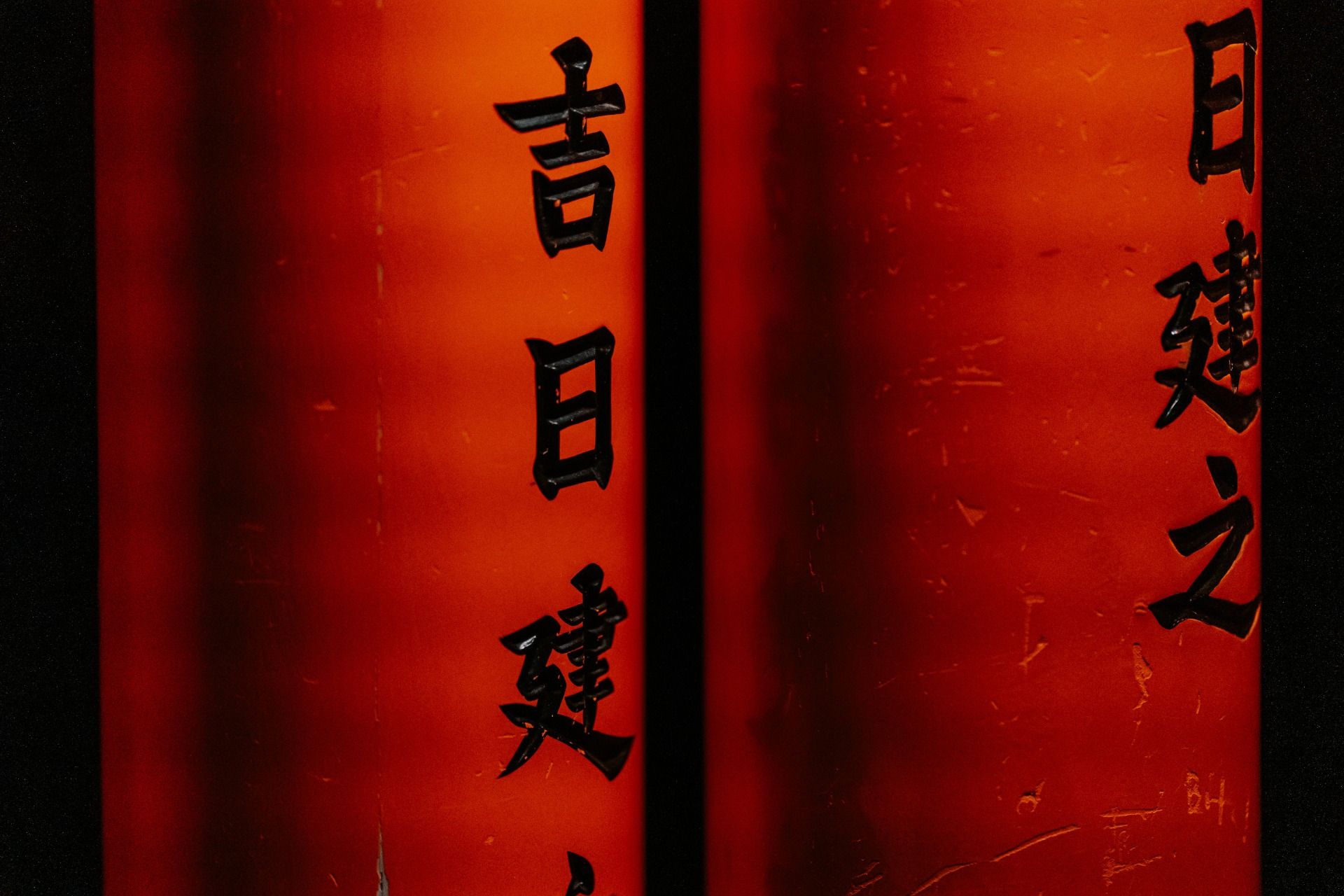

the Senbon Torii.

Over the years, the Senbon Torii had become something of Kyoto’s Eiffel Tower. On

guidebook covers and promotional posters, if not on every profile picture of

any visitor to Japan, photos of its thousands of vermilion gates could be found

virtually everywhere. Arguably, the torii paths across Fushimi Inari Taisha had

been photographed from every angle. In real-life, they could have lost their

magic. Yet, I stood as enticed as I had been the first time. Besides, the gates

were even more beguiling under the cover of night.

Lanterns were hanging on top of some of the toriis but most of them were plunged into

darkness. We were left with no choice than to follow the path on the right as

the one on the left was reserved for hikers going back to the main structures

and it seemed we were walking towards the unknown as we moved in an endless

corridor of carved red gates. The path was steep and winding, following the

curves of the mountain. Every few gates, we would leave the corridor to enter a

new one. There were 1000 gates along the main path so we knew we had a long way

ahead of us to see them all.

All around, all kinds of sounds reminded us that we were in the middle of a forest. In that

eerie atmosphere, we would have barely been surprised if a mythical kitsune had

come to life and sprung out of the woods. Walking in the woods alone at night

would have been the stuff of nightmare back home but we felt strangely serene

in that maze of bright toriis that acted like a safe cocoon. Perhaps the ones

who had donated these gates had felt safe there too, if they had come to the

shrine at all. They sure had felt hopeful that donating a torii would grant

them a wish. Some had even donated a torii in gratitude for a granted wish. The

names of these donors were now carved on the columns supporting each gate but

it wasn’t mentioned what their wishes had been.

A few hundred years later, Fushimi Inari Taisha was still a place of hope and

yearning. New toriis were no longer built along the path but a great many

mounds for private worship were to be found at the top of the mountain. Legend

also had it that the magic Omokaru stone could reveal if a wish would come true.

If the stone were lighter than one thought, the wish would be granted. If it

were heavier, the wish would remain unfulfilled.

Eventually, we neither climbed all the way to the top nor tried the stone’s magical

properties. At the end of the day, we still had to wake up early the next

morning to catch a plane back to France and no wishful thinking would allow us

to stay longer in Japan. Yet, our wish to visit one of Japan’s most famous

shrines in the most memorable way possible had been granted.